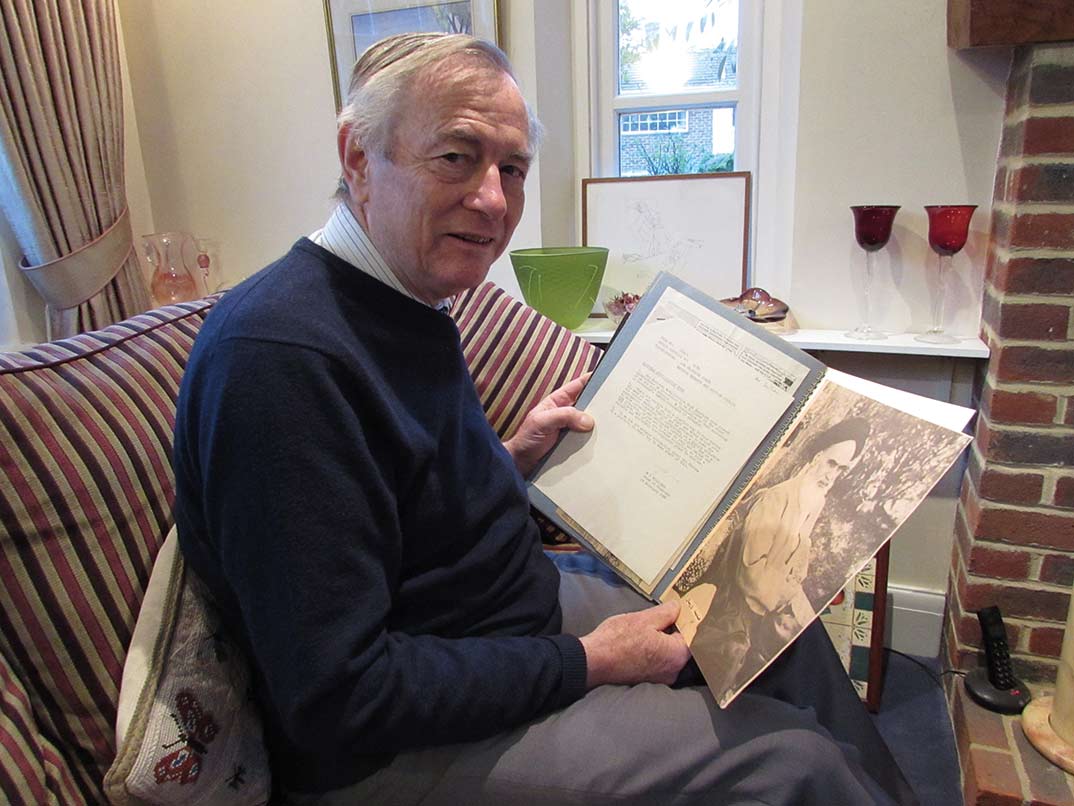

Singing with the Royal Tunbridge Wells Choral Society, Martin Williams seems perfectly at ease with retirement.

However, the impeccably-mannered bass singer, who has performed with the group over the past five years, has a remarkable story to tell.

During his Foreign Office career he, and his garishly-coloured Austin Maxi car, played a central role in rescuing US diplomats from the 1979 Embassy siege in the capital city of Tehran, which became one of the most dramatic incidents in modern political history. It threatened to utterly undermine already fragile relations between the Middle East and Western powers.

The Iranian attack has since received the full Hollywood treatment from actor and director Ben Affleck in the award-winning movie Argo. However, the film controversially claims the British failed to assist six US diplomatic personnel who had escaped capture in the incident.

Feeling compelled to set the record straight on events, Mr Williams, who now lives in Yalding, revealed that the airbrushed screen version of the siege could not be further from the truth, and he feels a sense of vindication that other more accurate accounts from people who were actually there have discredited the film’s interpretation.

As a senior British Foreign Office representative, Mr Williams was posted to Tehran in 1977, where he initially found the country in a comparatively stable and prosperous state. He was involved with commercial export operations, and could scarcely have imagined becoming engulfed in such a crisis.

The US embassy siege, which began on November 4, 1979, was to last an incredible 444 days. The six US diplomats all made it out alive, chiefly due to the initial rescue efforts by Mr Williams in his orange-coloured Austin Maxi, accompanied by a colleague, Gordon Pirie. The pair had been assigned the hazardous task of trying to find the US diplomats amid the chaos of a city experiencing revolution.

“I just thought it would be wrong not to put the correct situation on record over what happened.

“The Americans did acknowledge that we had given them help. One of the diplomats, Bob Anders, told the US press that the film was wrong, and that the British ‘had put their lives on the line for them’. It was generous of him to say that, but we had no doubt we needed to give assistance,” explained 74-year-old Mr Williams, who said the presentation of events in Argo had ‘bordered on slanderous’.

Despite the severity of the siege, the British diplomat says it was remarkable there were no fatalities during more than a year of tense negotiations that left its American targets constantly fearing the worst.

“All the Americans from the Embassy – around 50 staff – eventually got out safely, but there was certainly a risk of death, and lives could easily have been lost if things had gone wrong. They had a pretty awful time of it, and there were threats constantly uttered against them. They were in fear of their lives,” added Mr Williams.

One group was eventually smuggled out of the highly volatile situation in Iran under the unlikely guise of pretending to be film production crew, but the CIA kept details of the mission to rescue the stranded diplomats secret for more than 17 years.

Attack

Recalling the events in the build-up to the siege, Mr Williams said the situation had been deteriorating prior to the activists’ decision to lay siege to the US Embassy. It was claimed they did so in retaliation against American President Jimmy Carter’s decision to give Iran’s leader, the Shah, asylum at the height of the Iranian Revolution, which had begun in February that year, and which was marked by the return of exiled religious figurehead Ayahtollah Khomeini.

Mr Williams recalled how the British Embassy had already suffered an attack in November 1978, with the site partially set on fire, rocks thrown through office windows, cars ablaze in the streets and demonstrators besieging the compound. In true British understated fashion, Mr Williams described the episode, which made global headlines, as having been ‘rather worrying.’

Unsurprisingly, the whirlwind chain of events of the November 4 is etched particularly strongly in his mind. They began with renewed Iranian demonstrations at the US Embassy.

“We received a message saying there were diplomats who had escaped the siege who needed picking up. I was asked to go and find them using my car, a lurid coloured yellowish-orange Austin Maxi I had initially driven out to Iran in. I was out with colleague Gordon Pirie who took the Embassy Land Rover, though the directions weren’t clear and it took us some time to find them.

“We eventually found them in a residential area that we were not familiar with. There were five diplomats, including accompanying wives who had also been working in the visa section of the diplomatic service. They were all very worried as they had only been in the country for a few months. We decided to take them to our place, which was in a residential compound near the city.

“I phoned my wife Sue to say we were going to have guests to dinner. We brought the diplomats back and gave them a drink.”

The Americans were soon moved on for their own safety to the Canadian Embassy, along with another diplomat who had escaped the US Embassy siege and had been hiding out elsewhere within Tehran.

The group stayed with the Canadians for about two months and Mr Williams recalls how they were then given fake passports which had to be scrutinised by the Iranian Government to get approval. The ruse involved the Americans masquerading as a movie production crew scouting in Iran to find locations for a science-fiction film. This formed a large basis of the movie Argo.

He added: “This seemed pretty implausible, but it was something that had been worked out with the CIA. The Canadians looked after them, but there was a risk of them being found out. The Canadian Embassy closed down after that. We kept quiet about it as we didn’t want it to affect our work there.”

Beyond the US Embassy siege, Mr Williams was also heavily involved in ensuring British nationals were able to exit Iran as conditions deteriorated further. He was later awarded an OBE.

The extreme drama surrounding his posting in Iran continued after the Foreign Office was given a tip that the US Government intended to launch a rescue mission to free the remaining 50 embassy staff. The British diplomats were flown out just a day before what was to become an ill-fated mission.

This highly emotive chapter in diplomatic history was among Mr Williams’ most eventful in what proved an especially distinguished career. He continued to work around the globe, including travelling across the other side of the world to become the British High Commissioner to New Zealand, which itself brought with it a host of unexpected, yet rewarding challenges that have left him with some remarkable memories.

*In next week’s Times of Tunbridge Wells, Martin Williams gives an insight into his time as Governor of the Pitcairn Islands.

Martin Williams will be giving a Royal Tunbridge Wells Choral Society talk on his other diplomatic role, as Governor of the Pitcairn Islands, on March 18 at St John’s Church Hall, St John’s Road, Tunbridge Wells. For more information email: geraldchew@uclub.net

The society will also be performing A Sea Symphony, by Ralph Vaughan Williams at Tunbridge Wells Assembly Hall on April 23. Tickets £10-£24. Box office 01892 530613.