September sees the Gypsy Horse Fair take place in Horsmonden. It’s likely to attract 3,000 people and will yet again highlight ongoing issues between settled communities and travellers.

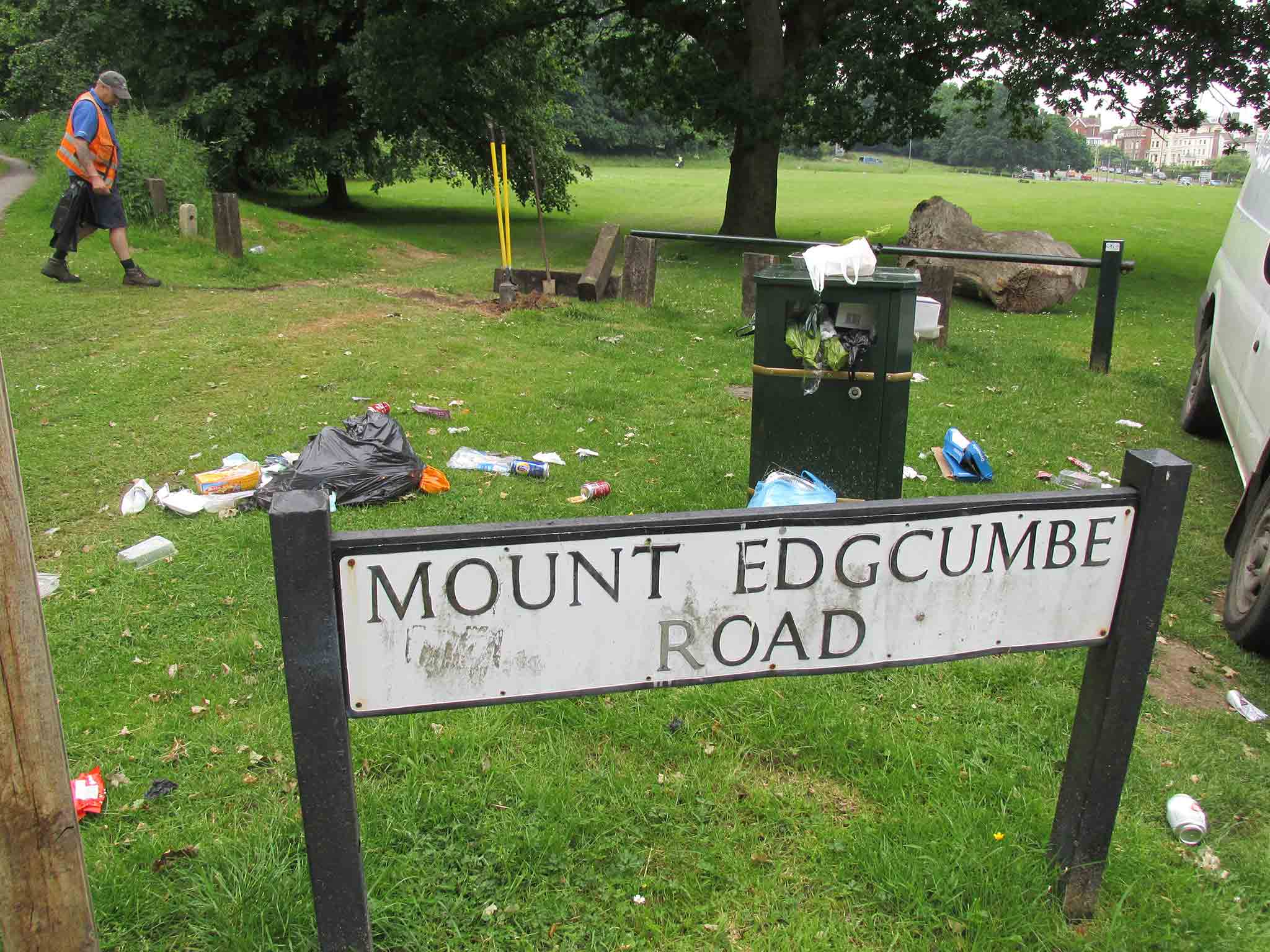

Last month saw the local council left with a £4,000 bill after travellers set up an illegal camp on Tunbridge Wells Common.

To find out the background to the whole matter we turned to Matthew Knight, the Senior Partner of Knights Solicitors in Tunbridge Wells. He has over 20 years’ experience of dealing with gypsies and travellers; principally for farmers, landowners and householders affected by unlawful incursions on their land, but also for local authorities seeking to manage gypsies and travellers in their area.

Here’s what he told us:

Tunbridge Wells has had its fair share of challenges when dealing with gypsies and travellers, and the mismanagement of this issue creates poor relations.

Gypsies and travellers lead a nomadic way of life in caravans and tents and there is legislation in place to work collaboratively with the 60,000-strong community for a mutually beneficial relationship. They have been a part of the economy since at least the 16th century and were, and still are to an extent, involved in seasonal agricultural work.

Labour, Coalition and Conservative governments have disagreed on how to accommodate this community in the past and this has resulted in a significant shortage of suitable pitches throughout England and Wales. As such about 20 per cent of gypsies and travellers are technically homeless (with no lawful place to station their caravans or pitch their tents).

Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) have been required under the Planning Policy for Traveller Sites (PPTS), a document produced by the Coalition government in 2012, to have a five-year supply of sites to meet the identified needs of gypsies and travellers ‘to ensure fair and equal treatment for travellers, in a way that facilitates the traditional and nomadic way of life of travellers while respecting the interest of the settled community’.

It is for the gypsies and travellers to apply for planning permission from the LPA for land that they own or control. As per paragraph five of the PPTS, LPAs must ensure they make their own assessments and work collaboratively to identify sites whilst protecting Green Belt land and sites protected under the Birds and Habitats Directives, Sites of Special Scientific Interest, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, National Parks and local green spaces from inappropriate development. Only in exceptional circumstances would an LPA deviate from this.

Gypsies and travellers sometimes settle illegally because the time required to get planning permission can be relatively long or there are simply no sites available. In doing so they can break criminal or civil law such as, when entering a third-party site, by breaking locks (criminal damage) and trespass (entering the property without permission) and, when staying on the site, by leaving waste.

Although police have powers to remove illegally settled gypsies and travellers they tend not to use them. Police can find them difficult to deal with as they can be abusive and rude and are often reluctant to move away when asked to do so.

In addition, sites that are dismantled in one place often crop up elsewhere, whether that is beside a public road or on someone else’s private property.

Complicating matters further is that itinerant gypsies and travellers do not have residential addresses and move around, often making it difficult to notify them of civil proceedings and to effect enforcement against them. This, however, does not excuse police inaction and they should be encouraged to use statutory powers when they are appropriate.

If gypsies and travellers illegally settle on private land this is a trespass and the owner can evict them under common law, seek damages and/or seek an injunction to prevent any further trespass. In case law it has been established that you must ask them to leave the land, after which the owner may forcibly remove them. If they have entered the land using violence or force they may be removed without previous requests. In removing trespassing gypsies and travellers reasonable, force may be used; this is a question of fact dependent on the individual case.

Using excessive force can give rise to a civil claim and caution must be used. If you decide to use your common law rights you should notify the police of your intention so that they may be present to prevent any breach of the peace. It is best to make use of private bailiffs who deal with gypsies or travellers on a regular basis.

Gypsies and travellers’ lifestyles lead them to face these issues regularly but this does not excuse their breaking the law. Moving forward, LPAs need to use their powers to ensure that there is space in suitable locations for gypsies and travellers to use. For example, a temporary site could be made available for use in moments of need. Ultimately this will lead to maintaining a mutually beneficial and more positive relationship between the settled and gypsy/traveller communities.

The difference

Gypsies are wandering or itinerant people at one time believed to originate from Egypt but now thought to have come from the north-western part of the Indian sub-continent. They have been present in England since at least the 16th century. Gypsies are also known as Romanies and they used to speak a separate language or dialect called Romany.

Travellers were originally homeless people living in Ireland whose wandering status originated from dispossession initially associated with the English plantation of Ulster, but also with the economic and social changes arising from the Civil War. Irish travellers tended to stay in Ireland and it is believed that they started to travel to Wales, Scotland and England in the 19th century – perhaps as a result of the potato famine.