Geoff Dann is a leading authority on the edible wild fungi of Northern Europe, and author of the most comprehensive book on that subject ever published. A local to the area, we asked Geoff where he goes to find the best forage in West Kent, and the answer’s not as simple as you might think

I am very familiar with the countryside of West Kent. I grew up just over the Surrey border in Caterham, cut my fungi foraging teeth thirty years ago on Limpsfield Chart, and a large proportion of the photos in my book were taken in West Kent and East Sussex. It ranks among the best places in the whole country for wild fungi, for reasons I’ll explore below, but first I need to explain why I can’t advise you on local foraging hotspots (well, I’ve already mentioned one, and that’s your lot.)

The first rule of fungi foraging hotspots: You do not talk about fungi foraging hotspots. The best locations for fungi foraging tend to be those that are frequented by no other foragers, or even better, aren’t frequented by anybody at all. Once a forager finds a good location (and quite often a good location is good for more than just one edible species), then, if they’ve got any sense, they’ll do their best to keep it a secret, forever. I only mentioned Limpsfield Chart because that one’s definitely out of the bag already – once upon a time I had the place to myself, but last time I was there, there were foragers all over the place. A general piece of advice, therefore, is the further you get away from London, the more likely you are to find some good stuff (and that’s just a numbers game – more people = less fungi).

The High Weald was one of the last parts of England to remain as an impenetrable wildwood, long after most of the English countryside had been tamed.

West Kent is, however, disproportionately good for fungi foraging, and the reasons are geological and historical. For those unfamiliar with local geology, the whole of southern England is an ‘anticline’ (an upswelling in the rocks), which was once completely covered with chalk. The highest part of that chalk, in the centre, has eroded away, leaving the North and South Downs as two roughly-parallel ridges of chalk hills. The area in between them is known as The Weald, and right in the centre there is another ridge of hills (the High Weald), this one composed mainly of sandstone – the oldest rocks that occur at the surface anywhere in south-east England.

The High Weald runs in a broad arc starting around Crawley/Horsham, and going via the Ashdown Forest and Heathfield down towards Battle (the very oldest exposed rocks can be found where this ridge meets the sea between Hastings and Rye). ‘Weald’ actually means ‘Forest’, and this area, especially the High Weald, was one of the last parts of England to remain as an impenetrable wildwood, long after most of the English countryside had been tamed. Even now, this area remains one of the most heavily-wooded parts of the country, although today much of this woodland is working forestry land rather than ancient woodland.

Why is this good for fungi?

- Firstly, the variety of fungi to be found in woodland is much greater than other habitats, especially if it is ancient woodland or mixed woodland.

- Secondly, the variety of fungi to be found on acidic, sandy soil is greater than other soil types.

- Thirdly, the slightly higher elevation of the High Weald means a slightly increased rainfall, which is also popular with many species of fungi.

Together, these factors make the woodland of the High Weald one of the very best places in the British Isles to go looking for fungi.

What exactly should you be looking for when foraging?

There are far too many for me to list here (hundreds of edible species), but there’s a specific habitat that is particularly abundant in West Kent, and that is pine forestry. This tends to be a monoculture, which are usually bad news for biodiversity, but the situation is a bit different for fungi. A lot of fungi are symbiotic with trees, and some species of tree have a greater diversity of associated fungi than others. And pine is probably the best tree species of all as far as fungi are concerned, so pine woodland is a particularly good place to go. If you’re lucky, you might just come across a real bonanza.

Think you’ve got the perfect spot in mind? Find out some of the edible species you can find there

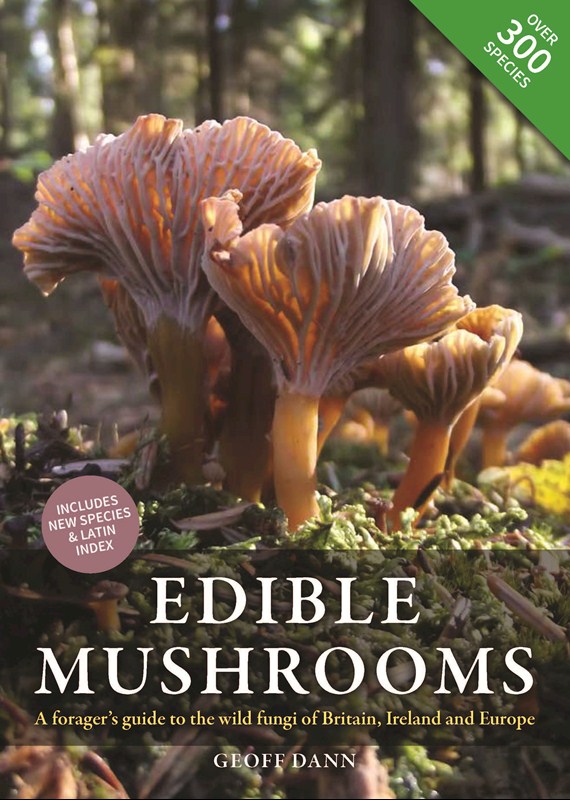

Geoff’s seminal text ‘Edible Mushrooms’ (Green Books) has been updated for 2018, and launches this June. Keep an eye out for the hardback version in your local bookshop.�